Once upon a time…

Don’t all the best fairy tales begin with this little bit of cliché? Yet there is a reason behind it, and even though 2000’s Chocolat opens and closes on this note, there is precious little in between that can be classified as cliché. In fact, so little of what unfolds in this film feels rote or expected, which adds to the mystical charm of this story based on the novel by English author Joanne Harris. Through the course of the narrative, it will pit paganism against Christianity and modernism against traditionalism and does so in a way that doesn’t alienate Christian values. The people we meet are not, in general, bad people, just stagnant, and a change comes to them, quite literally, on the north wind.

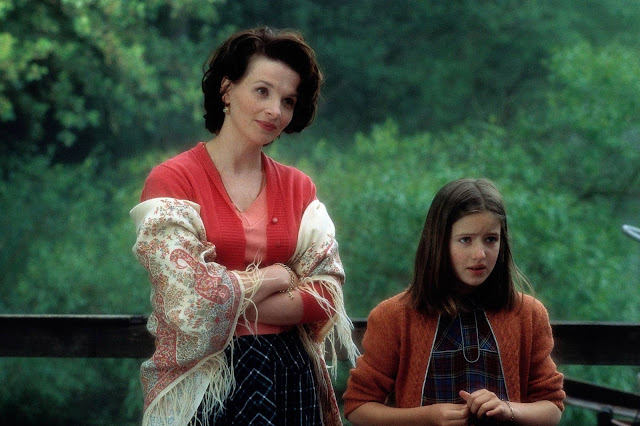

We are introduced to the film’s protagonist, Vianne (Juliette Binoche), as she and her six-year-old daughter Anouk (Victoire Thivisol - dubbed by Sally Taylor-Isherwood) arrive in a quiet French village in 1959. Vianne drifts with the wind, just as her mother before her, and she and Anouk have rarely spent long in any one place. Upon arrival, they rent a small shop from Armande Voizin (Judi Dench), an elderly woman who is estranged from her daughter Caroline (Carrie-Anne Moss) and is forbidden from seeing her grandson, Luc (Aurélien Parent-Koenig). There, she intends to open a chocolatery, much to the chagrin of the mayor of the town, Comte de Reynaud (Alfred Molina), a pious man who sees the chocolatery as temptation for the town as it is at the start of Lent.

Thus starts a personal crusade between Reynaud and Vianne as he uses his influence on the newly appointed village priest, Père Henri (Hugh O’Connor) to brand the chocolatier as sinful and a distraction from God. Reynaud, whose own wife has apparently left him— though he remains in denial of this— sees himself as the elected leader of the town’s immortal souls and is determined to lead them away from such evils as the husbandless Vianne and her shop of delicacies. Much gossip is spread about her being an atheist and having an illegitimate daughter, but slowly Vianne makes inroads with the townspeople and influences many of them to do things they never thought they would be able to do.

The film plays fast and loose with the idea that Vianne has some mystical powers to her, far more subtly than the novel it is based on. We get glimpses of this though in early scenes where she and Anouk use a sort of spinning plate as a form of a Rorschach test to help determine a person’s favorite treat. These predictions prove to be scarily accurate. This use of the plate, not found in the novel, goes away later in the film, yet the predictions do not. Vianne seems to represent the devil and temptation to this community, and she does nothing to dissuade that idea, even going as far as scheduling a fertility festival during Easter.

But Vianne represents more than that. She represents an emergence from stagnancy. This village seems to be living in the 1800s with its old-fashioned values and viewpoints. We can see this in the marriage of Joséphine (Lena Olin) and Serge (Peter Stormare). Serge is an alcoholic who abuses his wife, and when she finally flees from that abuse, it is looked upon, specifically by Reynaud, as a violation of her wedding vows. Vianne accepts her into her home and shows her that she can be more than just Serge’s put-upon wife. Meanwhile, Reynaud takes it upon himself to try and rehabilitate Serge through prayer and confession. To say that this ends up being fruitless would be an understatement.

The village is cloistered off, too. They don’t like outsiders, especially those with different values. Vianne is viewed with suspicion at first, but her shop of chocolate wins people over. This distrust is extended to Roux (Johnny Depp) and his group of “river-rats”, nomads that live in boats and travel up and down the river wherever they please. Roux and his people are unwanted, only allowed to stay because the law doesn’t provide the townsfolk with a legal alternative to run them out. Naturally, Vianne welcomes them in and even has a romantic dalliance with Roux. She may be an atheist, but a lot of what she represents is Christian charity.

This could be seen as a Garden of Eden parable or an example of The Left Hand of God. Either way, there is some religious magic going on that results in a betterment of the community as a whole. What Vianne represents is an introduction of energy into a stagnant community that was in desperate need of a kick in the pants. Just prior to her arrival, Père Henri was appointed, taking over for the previous priest who had been in that position for over five decades. Henri initially is being guided by Reynaud, who even extensively rewrites all of his sermons for him. But Henri is, himself, questioning the old ways and is relieved when he is finally given a chance to speak his own words from the pulpit. Various others in the community are touched, too, by Vianne and her chocolate. There’s Joséphine, of course, but also a townswoman who suffers from kleptomania. She also manages to start the healing process between Armande and her daughter, allowing Luc a chance to get to know his grandmother.

The biggest transition, though, is that of Reynaud. This is something that was made up for the film. Reynaud in the novel is a far darker character who saw himself superior to everyone else in the town and felt that it was his duty to lead them like sheep because they were too stupid to make their own decisions in life. While some of that is evident in the film, it has been softened a great deal in this adaptation. Two major things contribute to Reynaud’s change in the end. The first is his utter incapability to reform Serge. Though Reynaud’s motives are honorable, it is often impossible to reform an abuser, and that proves to be the case here. Serge tries to win back his wife by presenting himself as penitent and bringing her flowers, and fortunately, she doesn’t allow him back into her life. Later, he will break into the house she is sharing with Vianne, drunken and violent, nearly strangling Vianne in his attempts to force Joséphine to come back to him. Even later, he is responsible for setting a fire to the “River Rats’” boats, a fire that could have resulted in deaths. This latter act finally forces Reynaud to accept that Serge is beyond help, and he expels him from the village. The second thing that ultimately changes Reynaud is his own personal act of vandalism, an act that leads to a sort of revelation for him.

Chocolat is framed like a fairy tale, and to a degree, it is. Vianne and Anouk blow in on the north wind, and their intent is to leave the same way. But this is a tale where the heroine is changed by the town, too, and, at least for a while, she may set down her roots. It’s an odd, and somewhat disappointing, decision to add, for the film, a backstory that includes native superstitions and mysticism, especially since it feels incompatible with the casting of Juliette Binoche, but that is a minor hiccup in an otherwise beautifully told fable. There is subtext galore in this one and a hefty dose of allegory, but all of it is in service of a charming and disarming narrative that leaves you with a smile on your face, having been completely won over.

Academy Award Nominations:

Best Picture: David Brown, Kit Golden, and Leslie Holleran

Best Actress: Juliette Binoche

Best Supporting Actress: Judi Dench

Best Screenplay - Based on Material Previously Produced or Published: Robert Nelson Jacobs

Best Original Score: Rachel Portman

____________________________________________________

Release Date: December 22, 2000

Running Time: 121 Minutes

Rated PG-13

Starring: Juliette Binoche, Judi Dench, Alfred Molina, Lena Olin, Johnny Depp, Carrie-Anne Moss, John Wood, and Leslie Caron

Directed By: Lasse Hallström

Comments

Post a Comment