Remakes have been a thing since the beginning of motion picture history, and so, too, havepeople been complaining about them. Remakes aren’t going away anytime soon, and complaining about them misses the point of why they are made in the first place. Not all of them are soulless cash grabs with the intention of peeing on your childhood and ruining nostalgia. The best of them come about to improve on what couldn’t have been done the last time around due to lack of technology, budget, or just because the previous effort didn’t quite live up to expectations.

Ben-Hur was originally filmed as a silent short picture in 1907. This was a loose adaptation of the Lew Wallace 1880 novel Ben-Hur: A Tale of Christ and, at a mere 15 minutes, includes just a few highlights from the novel. In 1925, MGM Studios commissioned a feature-lengthremake that unfortunately was a trainwreck of a production, going months over schedule and costing more than any picture the studio had ever produced. The director was replaced,and large portions of the original footage was scrapped and re-shot, further ballooning the budget. What was finally released was a film that incorporated mostly new footage with a smattering of the initial shoot peppered in to take advantage of the location shooting in Rome, Italy. The film was a success, but the large budget limited profits and left a sour taste in the mouths of studio heads.

Fast forward to the 1950s, and MGM Studios once again took a stab at this epic biblical drama. Now, no longer limited by the silent era and with better filming techniques at their disposal, MGM once again set out to film Ben-Hur. The 1959 version would become for most people the definitive version of this massive story and one that many religious families would watch annually in much the same way as they did The Ten Commandments. Scenes that were exciting in the silent film were recreated in glorious technicolor and enhanced with MGM’s new 65mm widescreen process, a gimmick intended to compete with the rise in popularity of home televisions. In virtually every way, this version of Ben-Hur triumphs over the 1925 version, yet there are still some who prefer the older version. Special edition releases of the 1959 version include a copy of the 1925 version for anyone wanting to compare the two.

In more recent years, there has been a resurgence of interest in the source material, and two more versions were released: an animated film in 2003 that brought back Charlton Heston in the lead role of Judah Ben-Hur and a live-action adaptation in 2016 that replaced all the spectacle of the classics with a bunch of green screen and CGI. Neither version made much of an impact on modern audiences, with the 2016 version has been designated officially as a box office bomb. The animated film feels like a gimmick, cashing in on the nostalgia of Heston even as his life was winding down, and the 2016 version is an utter mess, distilling a four-hour epic into just over two hours. Everything in that version feels artificial,and it all looks like it was shot against a green screen, depleting any real sense of the epic scale of this story. When selecting a version of Ben-Hur to watch, the 1959 version should be the one to go to.

Ben-Hur tells the story of Judah Ben-Hur (Charlton Heston), a wealthy Jewish prince who lives with his mother, Miriam (Martha Scott), and younger sister, Tirzah (Cathy O’Donnell). Judah’s Roman childhood friend, Messala (Stephen Boyd), returns to Jerusalem as commander of the Fortress Antonia and embraces Rome’s glory and power while Judah is devoted to his people’s freedom and his faith. Messala demands Judah surrender potential rebels to the Roman authorities, but he refuses.

When the new Judean governor and his procession enter the city, Judah and his sister watch from the upper terrace. By accident, some loose tiles from the roof fall to the ground, spooking the governor’s horse, throwing him. Messala realizes it was accidental but condemns Judah anyway, sending him to the galleys and arresting Miriam and Tirzah. As Judah is being marched through the desert to the galleys, they pass through Nazareth,where, collapsing from lack of water, he is revived when a carpenter gives him a drink. This will be the first of many encounters Judah will have with this carpenter.

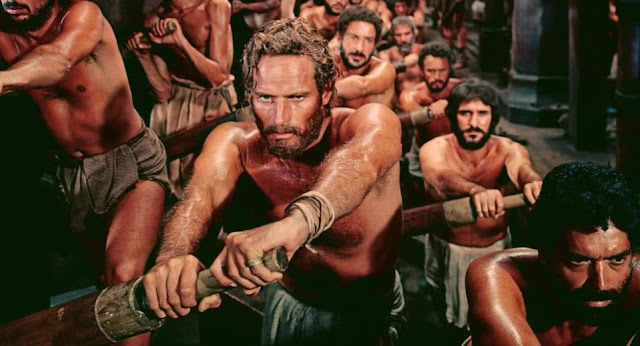

The story follows Judah Ben-Hur as he is chained up and forced to be a galley slave for several years, then is granted his freedom by his master, Arrius (Jack Hawkins), after Judah risks his life to save Arrius during an attack. Arrius frees Judah and adopts him as his son. He becomes a skilled chariot racer but turns down an offer to race against several others,including Messala, until he is intentionally misinformed that his mother and sister are dead. In actuality, they were imprisoned for a while but now have been set free to die from leprosy. The lie that they had died was to keep Judah from finding them in their debilitated condition. Judah, further angry by their “deaths,” agrees to the race. He triumphs, and Messala is killed, revealing in his dying breath that Judah’s mother and sister yet live.

This is a story about perseverance and faith, told adjacent to several Biblical stories in such a way as to not focus on the narrative of the Bible but have those moments happening just off-screen. Occasionally, a famous moment in the life of Jesus Christ happens that will nudge Judah Ben-Hur closer to a realization that he has been in the presence of the Son of God, such as when he witnesses the Sermon on the Mount or the crucifixion. The film will end on a miracle as Judah finally is able to return home only to find that his family has been cured of their leprosy. Judah will learn over the course of the film that forgiveness is better than vengeance, and a big part of that lesson comes from his witness of Christ.

Ben-Hur may not be as religiously rewatched annually as The Ten Commandments is, but in its own way, it is just as powerful of a religious film as Cecil B. DeMille’s Old Testament epic is. Its epic length may dissuade some people from tackling the film, but that shouldn’t stop people from watching it or going for the more recent version simply to save some time. The 1959 Ben-Hur is in every way superior to the 2016 version, even if it is more of an investment in time to watch it. It is especially moving for Christian viewers who will see the spiritual growth Judah Ben-Hur will go through over the course of the film and recognize the conversion they themselves felt when they first embraced Christianity into their lives. This film has more going for it than merely the spiritual lessons, too. It’s a beautiful film to look at,and the scale of things is impressive. The chariot race has yet to be matched in modern cinema thanks to some truly impressive stunt work and production values. It is definitely one of the highlights in an already impressive looking film. Compare it to the chariot race in the remake, and it becomes obvious that better effects do not equate to a more impressive sequence.

This film is nearly seventy years old now, but it has stood the test of time. In a world where religion and faith come under more and more scrutiny and scorn, it is nice to look back on a film like this that celebrates faith and conversion without being satirical or sarcastic. This is a film that has a message that is interwoven throughout and never really loses sight of that message even as the complex narrative plays out. The novel was beloved when it wasreleased in 1880, and I cannot imagine a better film version could be made based on this material. It is a celebration of Christ and his teachings while also showcasing the best of what Hollywood can produce when given the right materials and open reign to make a truly epic motion picture.

Academy Award Nominations:

Best Picture: Sam Zimbalist (won)

Best Director: William Wyler (won)

Best Actor in a Leading Role: Charlton Heston (won)

Best Actor in a Supporting Role: Hugh Griffith (won)

Best Art Direction - Set Decoration - Color: Edward C. Carfagno, William A. Horning, and Hugh Hunt (won)

Best Adapted Screenplay: Karl Tunberg

Best Cinematography - Color: Robert L. Surtees (won)

Best Costume Design - Color: Elizabeth Haffenden (won)

Best Film Editing: John D. Dunning and Ralph E. Winters (won)

Best Sound Recording: Franklin Milton (won)

Best Music - Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture: Miklós Rózsa (won)

Best Special Effects: A. Arnold Gillispie, Robert MacDonald, and Milo Lory (won)

____________________________________________________

Release Date: November 18, 1959

Running Time: 222 Minutes

Not Rated

Starring: Charlton Heston, Jack Hawkins, Haya Harareet, Stephen Boyd, Hugh Griffith, Martha Scott, Cathy O’Donnell, and Sam Jaffe

Directed By: William Wyler

Comments

Post a Comment